1.984467454426692PSTAT 5A: Lecture 19

Regression Part II, and an Intro to Sampling Techniques

Ethan P. Marzban

2023-06-06

Review of Regression

Review of Lecture 18

Last time, we started to talk about how to actually model a relationship between two variables.

Specifically, given a respone variable

yand an explanatory variablex, we typically assumexandyare related through the equation \[ \texttt{y} = f(\texttt{x}) + \texttt{noise} \] where \(f\) is some function.Of particular interest to us in this class is when \(f\) takes the form of a linear equation: i.e. when our model is of the form \[ \texttt{y} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \cdot \texttt{x} + \texttt{noise} \]

Review of Lecture 18

Now, the noise part of our model makes it impossible to know the true values of \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\).

- In this way, we can think of them as population parameters.

As such, we sought to find point estimators \(\widehat{\beta_0}\) and \(\widehat{\beta_1}\) that best estimate \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\), respectively.

To quantify what we mean by “best”, we employed the condition of minimizing the residual sum of squares.

- Effectively, this means finding the line \(\widehat{\beta_0} + \widehat{\beta_1} \cdot \texttt{x}\) that minimizes the average distance between the points in the dataset and the line.

Review of Lecture 18

Review of Lecture 18

Such estimators (i.e. those that minimize the RSS) are said to be ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates.

- The resulting line \(\widehat{\beta_0} + \widehat{\beta_1} \cdot \texttt{x}\) is thus called the OLS Regression Line

It turns out that the OLS estimates of \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\) are: \[\begin{align*} \widehat{\beta_1} & = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} (x_i - \overline{x})(y_i - \overline{y})}{\sum_{i=1}^{n} (x - \overline{x})^2} = \frac{s_Y}{s_X} \cdot r \\ \widehat{\beta_0} & = \overline{y} - \widehat{\beta_1} \cdot \overline{x} \end{align*}\] where r denotes Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient \[ r = \frac{1}{n - 1} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left( \frac{x_i - \overline{x}}{s_X} \right) \left( \frac{y_i - \overline{y}}{s_Y} \right) \]

Example

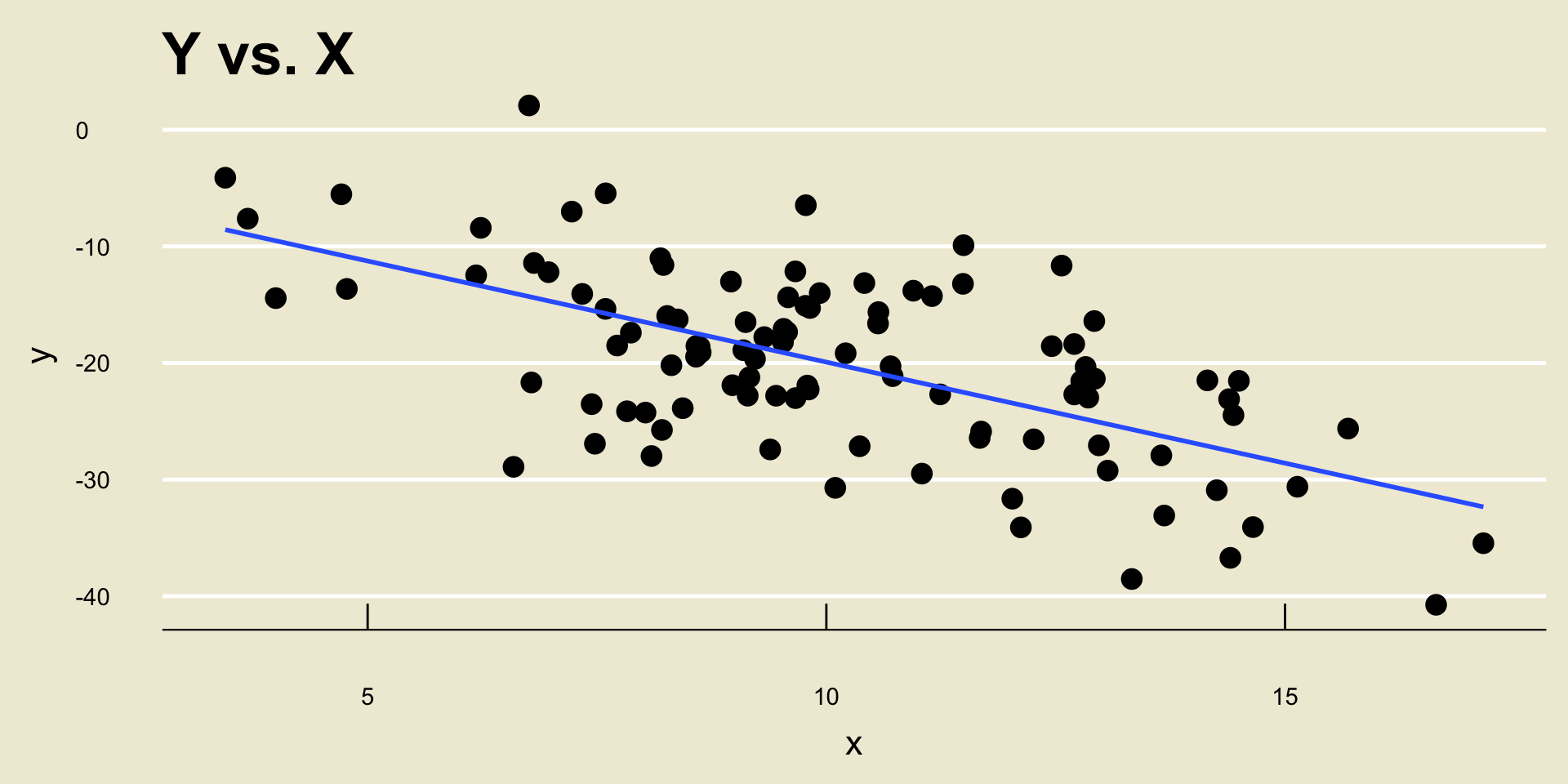

- \(\widehat{\beta_0} =\) -2.5884231; \(\widehat{\beta_1} =\) -1.733778

Example

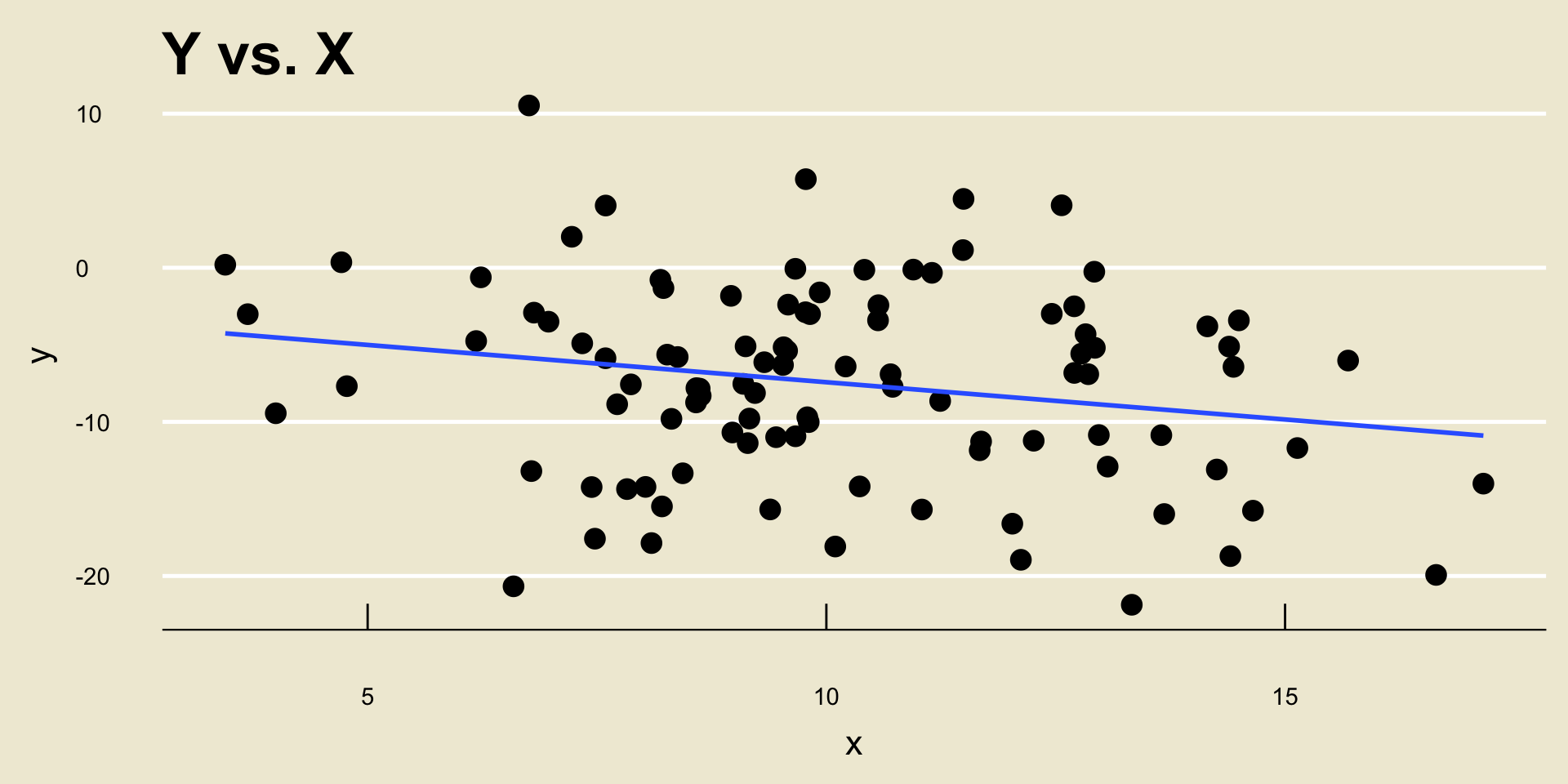

- \(\widehat{\beta_0} =\) -2.5884231; \(\widehat{\beta_1} =\) -0.483778

Example

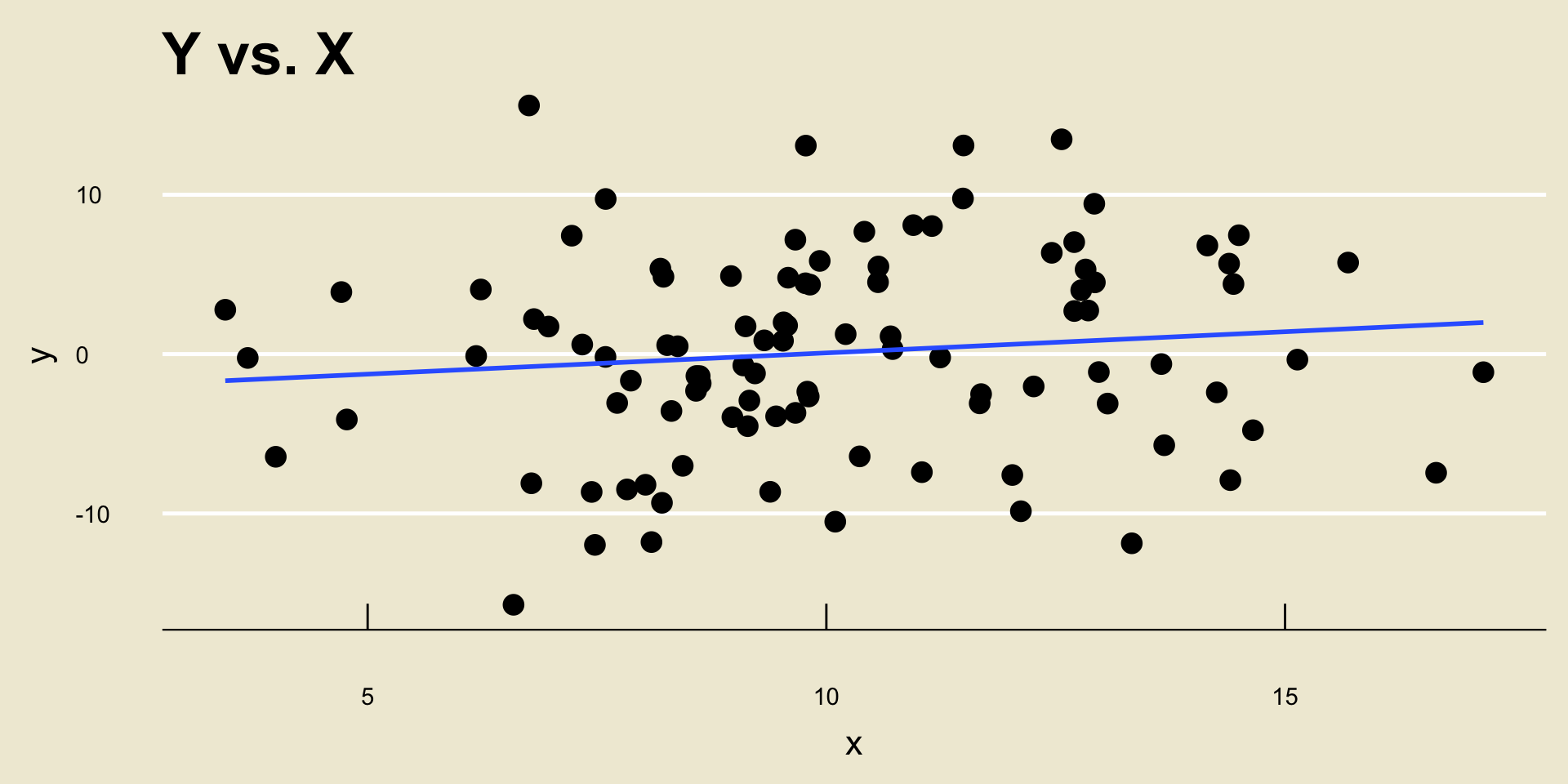

\(\widehat{\beta_0} =\) -2.5884231; \(\widehat{\beta_1} =\) 0.266222

Do we really believe the slope, though?

Leadup

Well, remember- \(\widehat{\beta_1}\) is just an estimator of \(\beta_1\), the true slope.

As such, we should be a little wary of using a single observed instance of \(\widehat{\beta_1}\) as an estimate for \(\beta_1\).

What do you think would be a better quantity to report?

That’s right- a confidence interval!

Confidence Intervals for the Slope

It is often desired to report a confidence interval for \(\beta_1\).

Recall: in general, a confidence interval for a parameter \(\theta\) takes the form \[ \widehat{\theta} \pm c \cdot \mathrm{SD}(\widehat{\theta}) \] where:

- \(\widehat{\theta}\) is a point estimator for \(\theta\)

- \(c\) is a constant that depends both on the confidence level as well as the sampling distribution of \(\widehat{\theta}\).

Confidence Intervals for the Slope

We’re going to do the same thing for \(\beta_1\): \[ \widehat{\beta_1} \pm c \cdot \mathrm{SD}\left( \widehat{\beta_1} \right) \]

You will not be responsible for computing the standard deviation of \(\widehat{\beta_1}\). On a problem, you will be provided with this information.

We should, however, talk about what distribution \[ \frac{\widehat{\beta_1} - \beta_1}{\mathrm{SD}(\widehat{\beta_1})} \] follows, as this will be the distribution whose quantiles we use when constructing our confidence intervals.

Confidence Intervals for the Slope

It turns out that, if we assume the noise in our model is normally distributed, then \[ \left( \frac{\widehat{\beta_1} - \beta_1}{\mathrm{SD}(\widehat{\beta_1})} \right) \sim t_{n - 2} \]

- Don’t worry too much about why we use \(n - 2\) degrees of freedom instead of \(n - 1\). The reasoning depends a bit on the way we compute \(\mathrm{SD}(\widehat{\beta_1})\), which, again, we will not discuss in this class.

This allows us to construct confidence intervals for \(\beta\) using the \(t_{n - 2}\) distribution.

Worked-Out Example

Worked-Out Example 1

Two sets \(\boldsymbol{x} = \{x_i\}_{i=1}^{100}\) and \(\boldsymbol{y} = \{y_i\}_{i=1}^{100}\) have yielded: \[\begin{align*} \sum_{i=1}^{100} x_i = 1009.491 & \qquad \sum_{i=1}^{100} y_i = -2009.075 \\ \sum_{i=1}^{100} (x_i - \overline{x})^2 = 796.16 & \qquad \sum_{i=1}^{100} (y_i - \overline{y})^2 = 6237.68 \\ \sum_{i=1}^{100} (x_i - \overline{x})(y_i - \overline{y}) = -1380.372 \end{align*}\]

- Find the equation of the OLS regression line.

- It turns out that \(\mathrm{Var}(\widehat{\beta_1}) = 0.0452\). Construct a 95% confidence interval for \(\beta_1\), the slope of the true linear relationship between

xandy.

Solutions

For part (a), we simply plug into our formulas: \[\begin{align*} \widehat{\beta_1} & = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} (x_i - \overline{x})(y_i - \overline{y})}{\sum_{i=1}^{n} (x_i - \overline{x})^2} = \frac{-1380.372}{796.16} \approx \boxed{-1.73} \\ \widehat{\beta_0} & = \overline{y} - \widehat{\beta_1} \cdot \overline{x} = \left( \frac{-2009.075}{100} \right) - (-1.734) \cdot \left( \frac{1009.491}{100} \right) \approx \boxed{-2.627} \end{align*}\]

Hence, the equation of the OLS regression line is \[ \boxed{ \widehat{y} = -2.627 - 1.734 \cdot \texttt{x} } \]

Solutions

For part (b), we should first find the appropriate quantile of the appropriate t-distribution.

Here, \(n = 100\) meaning we will use the \(t_{98}\) distribution.

Additionally, we require a 95% confidence level, meaning the quantile we seek is the \(97.5\)th percentile or, equivalently, negative one times the \(2.5\)th percentile.

Solutions

- Therefore, our confidence interval for \(\beta_1\) takes the form \[ (-1.734) \pm 1.98 \cdot (\sqrt{0.0452}) = \boxed{[1.313 \ , 2.155]}\]

A CI that Contains Zero

What happens if a confidence interval for \(\beta_1\) includes zero?

Well, let’s think about what a confidence interval is actually saying.

A 95% CI \([a \ , b]\) for some parameter \(\theta\) is saying “we are 95% confident that the true value of \(\theta\) lies in the interval \([a \ , b]\).”

As such, if a 95% confidence interval for \(\beta_1\), we are effectively saying that the value of \(\beta_1\) could be zero.

Since \(\beta_1\) represents the slope of the relationship between

xandy, this means we are saying that there could potentially be no relationship betweenxandyat all!

Hypothesis Testing for the Slope

Indeed, we could make this a bit more rigorous by performing a hypothesis test for \(\beta_1\).

- Quick side note: there is in fact a duality between confidence intervals and hypothesis testing. For the sake of time and brevity, however, we will likely not get a chance to discuss this connection this quarter.

Specifically, we may wish to test \[ \left[ \begin{array}{rr} H_0: & \beta_1 = 0 \\ H_A: & \beta_1 \neq 0 \end{array} \right.\]

Hypothesis Testing for the Slope

A natural test statistic is \[ \frac{\widehat{\beta_1}}{\mathrm{SD}(\widehat{\beta})} \stackrel{H_0}{\sim} t_{n - 2} \]

Since we are considering a two-sided alternative (for now), our test would reject for large values of \(|\mathrm{TS}|\), where the critical value comes from the \(t_{n - 2}\) distribution.

- Or, we could simply consider p-values!

Hypothesis Testing for the Slope

- Indeed, many computer softwares (and statistical papers!) report a table resembling the following after running a regression:

| Estimate | Std. Error | t-value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -2.588 | 2.327 | -1.112 | 0.269 |

| Slope | -1.734 | 0.222 | -7.811 | 6.41e-12 |

The first column is the raw estimated value (i.e. \(\widehat{\beta_0}\) and \(\widehat{\beta_1}\), respectively)

The second column is the standard error (i.e. standard deviation) of the estimator

The third column is the test statistic (i.e. the first column divided by the second)

The fourth column is the p-value in a two-sided test, testing whether or not the given parameter is actually zero or not.

Extensions

Regression truly is one of the workhorses of statistics (the other being Hypothesis Testing).

Indeed, there is so much one can do with regression!

For one, we could consider how a response variable

yis related to multiple covariatesx1,x2, …,xk.We could also explore nonlinear relationships between

yand a single covariatex(or even multiple covariates!)

Extensions

Here is an interesting project: suppose we have access to a roster of passengers on the Titanic.

- For those who don’t know, the RMS Titanic was a British passenger line that crahsed into an iceberg on April 15, 1912.

Tragically, not all passengers survived.

One question we may want to ask is: how did various factors (e.g. class, gender, etc.) affect whether or not a given passenger survived?

- For instance, since women and children boarded lifeboats first, it may be plausible surmise that women and children had a higher likelihood of surviving.

Extensions

Notice how here, the response variable (i.e. whether or not someone survived) is a binary variable; that is, it takes only one of two values (

survivedordid not survive).Regression involving a binary response (like with this Titanic project) is called logistic regression and is highly applicable to lots of other projects as well.

- By the way, there is an actual dataset on the Titanic at https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/titanic

These are all topics that fall under the category of Machine Learning.

- I highly encourage everyone to take a look at some Machine Learning resources, either online or by way of PSTAT 131!

Where Does Data Come From?

Where Does Data Come From?

Throughout this course, we have been using various pieces of data.

One thing we should discuss, as good Data Scientists, is where this data actually came from?

- Who collected it? How was the data collected? Who were the subjects included in the data?

We will now begin to discuss some possible answers to these questions, as well as some practical strategies for collecting data of our own!

The Research Process

Indeed, most experiments and studies begin with some sort of question.

- For example: “does this new drug truly reduce blood pressure?”

- Or: “is smoking really linked with higher rates of lung cancer?”

- Or: “what is the average mercury content in swordfish in the Atlantic Ocean?”

- Or: “over the past 3 years, what is the average number of people that have been admitted into the PSTAT major?”

The next step is something we’ve actually done several times in this class already: identify the population of interest!

- Can anyone tell me what the populations associated with the above research questions are?

Sampling Procedures

Now, we need the most crucial piece of all: data!

- Specifically, we need to collect our data.

This will entail taking a sample (or possibly many samples) from our population.

There are many ways to take a sample!

One way is to take what is known as a simple random sample (or SRS, for short).

A simple random sample is akin to assigning a unique number to each person in the population, and then picking some subset of these numbers uniformly at random.

- Crucially, in this way, each member of the population has an equal chance of being included in the sample.

Sampling Procedures

Now, Simple Random Samples do have some potential downsides.

As an example, let’s consider the following situation: suppose our population is the workplace at some company (which we will call Company X).

Say we are interested in determining whether or not there is systemic racism present in Company X.

To determine whether or not this is the case, we might take a sample and administer a survey (we’ll talk more about surveys in a bit).

Can anyone tell me a potential problem with this setup if we were to take a Simple Random Sample?

- What if I tell you, for example, that 80% of people in this company are Caucasian and only 20% are not?

Sampling Procedures

That’s right- we run the risk of obtaining a biased sample.

Said differently: if we take an SRS of employees at this company, there is a high probability that this sample will contain a disproportionately larger number of Caucasians than non-Caucasians.

- This would almost certainly affect the results of our survey!

One way to remedy this would be to perform what is known as in which we first divide the population into several strata (i.e. groups), and then take an SRS from each stratum.

This has the benefit of ensuring a roughly equal number of participants from each stratum, but has the downsides of being very dependent on the strata that are created.

That is, sometimes it won’t necessarily be obvious how to divide the population!

Sampling Procedures

Another type of sampling is called cluster sampling. Similar to stratified sampling, the population is first divided into several groups (now called clusters). But, instead of taking an SRS from every cluster we instead take an SRS of clusters and then take an SRS from each included cluster

Note, then, that we are not including every cluster in our sample in this way of sampling.

This has the benefit of being (potentially) cheaper, but has the (obvious) downside of potentially skewing results due to the lack of certain clusters.

By the way, this is slightly different than the notion of Cluster Sampling outlined in the textbook; the textbook calls the above scheme “multistage sampling”. However, this term is not widely used, and as such we will simply refer to the above as “Cluster Sampling”, as most statisticians do.

Example

- Let’s consider an example from the textbook:

Example (credit to OpenIntro Statistics)

Suppose we are interested in estimating the malaria rate in a densely tropical portion of rural Indonesia. We learn that there are 30 villages in that part of the Indonesian jungle, each more or less similar to the next. Our goal is to test 150 individuals for malaria. What sampling method should be employed?

At surface level, an SRS may seem tempting.

- After all, the villages are “more or less similar to the next”.

However, an SRS will likely contain individuals from all (or certainly most) of the villages.

This would require someone to actually visit these villages to collect data, which will be incredibly costly.

As such, an SRS is probably not a good idea.

Example

Indeed, cluster sampling seems to be the way to go.

Specifically, we could assign each village to its own cluster, then select some number of villages (say, maybe 15 or so) randomly, and then select some number of people (say, 10 or so) from each of the selected villages.

Because the villages are “more or less similar”, the people included in our sample would likely not have many obvious differences (in the context of the experiment) and we would believe our sample to be relatively representative.

Additionally, the experimenter (or a volunteer) would only need to visit 15 villages instead of all 30.

Of course, we would need to modify our statistical tools slightly to reflect the fact that our sample was actually collected via a clustering scheme- such modifications (though not too challenging) are outside the scope of this course.

- Right now, I’m merely trying to get us to think about the practicalities of data collection!

Bias

Even if we end up with a fairly representative sample, there are ways bias can creep in.

Suppose we administer a survey to a representative sample of people.

It is not guaranteed that everyone in our sample will actually fill out the survey; even if a particular individual does attempt the survey, there is no guarantee they will finish the entirety of the survey.

This can lead to gaps in our data with respect to certain demographics, which is itself a form of bias.

We call this non-response bias.

Bias

Another sampling strategy that is prone to bias is known as convenience sampling.

We can think of convenience sampling as any sort of sampling scheme where individuals who are easily accessed have a higher chance of being included in the sample.

For example, suppose we poll students about their views on the housing crisis in Santa Barbara.

If we conduct this poll at UCSB, we are more likely to get UCSB students and much less likely to get, say, UCLA students.

Similarly, if we conducted our study at UCLA, we would be more likely to include UCLA students than, say, NYU students.

Bias

So, why would we ever use a convenience sample?

Well, as the name suggests- it is convenient!

Convenience samples are often both the easiest to obtain, as well as the cheapest.

Having said that, most statisticans agree thate convenience samples are bad. This is due to what is known as the garbage in garbage out philosophy.

Loosely speaking, the “garbage in garbage out” philosophy states that our results are only as good as our data- even the most sophisticated statistical models will output nonsensical or skewed results if we are feeding them nonsensical or skewed data!

Another Distinction

There is another distinction we should be aware of: the difference between an observational study and an experiment.

In an observational study, no treatment is ever explicitly applied (or withheld).

This is in contrast to an experiment, in which researchers assign treatments to cases.

For example, suppose a researcher is interested in determining the relationship between cancer rates and tanning beds.

In an experiment, the researcher would take some sample of volunteers, split them into groups, and assign one group to tan regularly and another to not use tanning beds at all for the duration of the study.

- At the end of the study, the researcher would collect data and analyze.

Another Distinction

If instead the researcher were to conduct an observational study, they might take some sample of people who already use tanning beds, analyze cancer rates, and repeat for a sample of people who do not use tanning beds.

- Note that in this case, the experimenter has not explicitly assigned a treatment (i.e. using a tanning bed) to either group. In a sense, the groups were formed around the treatment.

Naturally, experiments come with all sorts of ethical considerations.

For instance, in trying to determine the relationship between cancer rates and smoking, nobody would actually force a group of participants to smoke, just for the purposes of an experiment.

This is one “pro” in favor of observational studies- the experimenter is not responsible for forcing a group of people to do (or not do something) they wouldn’t want to.

Another Distinction

Of course, observational studies are not perfect either.

Specifically, observational studies cannot be used to identify causal relationships; they can only ever identify associations (or a lack thereof).

Remember that assocations are not the same things as causation!

- So, just because an observational study indicates a link between smoking and increased lung cancer rates, that is not sufficient justification to say that smoking causes increased lung cancer rates. To make that causal claim, an experiment would need to be conducted.

Example

Example (OpenIntro Statistics, 1.19)

A large college class has 160 students. All 160 students attend the lectures together, but the students are divided into 4 groups, each of 40 students, for lab sections administered by different teaching assistants. The professor wants to conduct a survey about how satisfied the students are with the course, and he believes that the lab section a student is in might affect the student’s overall satisfaction with the course.

- What type of study is this?

- Suggest a sampling strategy for carrying out this study.

Solutions

Because treatment has neither been administered nor withheld by the researcher, this is an example of an observational study.

In this case, stratified sampling would likely be a good idea, with each lab section assigned to a stratum. This ensures each stratum (lab section) is represented in the sample.

Longitudinal vs. Cross-Sectional Studies

Suppose a particular drug claims to significantly reduce blood sugar levels. Consider the following two scenarios:

An SRS of 100 people is taken from a certain demographic, and divided randomly into two groups: group A and group B. Group A is administered the drug and Group B is not administered the drug. After a week, the researcher collects data on the blood sugar levels of the two groups.

An SRS of 50 people is taken from a certain demographic. These 50 people have their blood sugar levels recorded, and are then all administered the drug. A week later, the participants have their blood sugar levels recorded.

Longitudinal vs. Cross-Sectional Studies

Note that both of these situations seemingly end up with the same data: 50 measurements of pre-treatment blood sugar levels, and 50 measurements of post-treatment blood sugar levels.

However, we can see that these two studies are fundamentally different.

In the first study, people were divided into two groups (called the treatment and control groups, respectively).

In the second, the same 50 individuals were tracked over time.

This is an example of the distinction between a cross-sectional study and a longitudinal study.

Longitudinal vs. Cross-Sectional Studies

In a longitudinal study, the same set of individuals is tracked over time.

In a cross-sectional study, individuals are divided into several groups.

Notice that data in longitudinal studies necessarily possess serial correlation: that is, measurements are correlated!

- Pre-treatment measurements for, say, John, are very likely correlated with John’s post-treatment measurements since these measurements were still collected from John!

Principles of Experimental Design

Let’s quickly return to our distinction between observational studies and experiments.

Suppose it is decided that we want to conduct an experiment.

We then need to think very carefully about how we want to design our experiment.

This leads us into our final discussion for this course: Experimental Design.

Treatment vs. Control Groups

First, let me make clear the distinction between treatment and control groups.

Treatment groups are groups to which one or more treatments is/are administered.

- There can potentially be multiple treatment groups; for example, we could have 4 groups each testing a different medicine

Typically, we always leave at least one group “alone”; i.e. one group to which no treatment is administered. This group is called the control group.

- It is also possible to have multiple control groups!

Experimental Design

Experimental Design loosely refers to the principles of and procedures related to setting up an experiment.

I won’t go into this in too much detail.

I do highly encourage you to read Section 1.4 of your textbook, as it provides a very nice summary of some of the main tenants of experimental design.

Remember - as Data Scientists, it is very important we understand our data as much as possible before performing analyses.

- Part of knowing our data is knowing how it was collected, and, indeed, how we might go about collecting our own!

What Now?

What Now?

Alright, so that was the last bit of new material I wanted to cover in this class.

But…. why did we do all of this?

What was the point of this course?

- If you say “the point was for me to finish my major”, well, then, fair enough!

But, more fundamentally, this course is designed to try and provide an introduction to Data Science.

What Now?

The key operating word in this is “introduction-” we only just scratched the surface of the topics we discussed!

Even within our own PSTAT department, there are lots of different courses that dive deeper into the subjects we discussed.

PSTAT 120A provides a deeper look at Probability, and some more sophisticated probability tools.

PSTAT 120B and 120C provide a deeper look at inferential statistics, and how to answer much more interesting and complex problems than those we looked at in this course!

Interested in Experimental Design? PSTAT 122 is devoted entirely to that!

Want to learn more about regression (including logistic regression)? Take PSTAT 126 and 131!

Story

Now, I know many of you are graduating this quarter.

- Congratulations, by the way!!!

For those of you who are not, and especially for those of you who aren’t quite sure what you want to do, I’d like to leave you with a story.

I encountered a student who had come into undergrad not knowing what they wanted to do at all.

They had a vague inkling that they might want to do math, but after a quarter switched to Econ, then Physics, and finally wound their way into the equivalent of PSTAT 5A at their undergraduate institution.

By the end of the quarter, they were so intrigued to learn more the decided to take the analog of 120A, and then 120B, and then, before they knew it, they had completed a degree in statistics!

Story

That student…. was me!

Years ago, I stumbled into the analog of PSTAT 5A and was so enamored by the field that here I am now, pursuing a PhD in it!

I truly believe statistics and data science are some of the most useful and applicable fields around.

Wherever there is data, there is the need for a data scientist.

Whenever there is uncertainty, there is the need for a statistician.

Statistics and Data Science have far reaching applications in so many fields!

Story

- There is a famous quote from an extremely influential statistician named John Tukey:

The best thing about being a statistician is that you get to play in everyone’s backyard.

I couldn’t agree more!

- Though, I would perhaps update this quote to say “statistician and/or data scientist”

So, now that you’ve learned the basics…

…go out and play!

Thank you for a great quarter!